It depends whether you are a purist or not. When people make this distinction they mean that conducting includes putting people right whereas bob-calling is what it says, just putting in the calls.

It depends whether you are a purist or not. When people make this distinction they mean that conducting includes putting people right whereas bob-calling is what it says, just putting in the calls.The Tower Handbook

You may have plenty of people now in your tower who can conduct, but will you always? What if they are all away? What if they move home? Conducting does not require super human skills. Any competent method ringer can learn the basics. When you do begin to conduct, you will find you actually understand what is happening in the method better, as well as being an asset to the band.

It depends whether you are a purist or not. When people make this distinction they mean that conducting includes putting people right whereas bob-calling is what it says, just putting in the calls.

It depends whether you are a purist or not. When people make this distinction they mean that conducting includes putting people right whereas bob-calling is what it says, just putting in the calls.

It is more helpful to recognise that there are many levels of conducting from knowing when to say go and stop, right through to knowing where all the other ringers are all the time. Most of us are somewhere in the middle of this range. There are no sharp dividing lines. The humble bob-caller may be able to put right the bell he was dodging with and the most proficient conductor who seems to know it all may occasionally come unstuck and not be able to sort things out.

Look at the different ways a touch can be set out, see section 15, figure 15.3. Each style supports a different way of thinking about the touch, and learning it. The main differences concern the length of the touch and whether there is a framework of (mainly) unaffected bells, usually the tenors. Short, simple touches without a fixed bell framework use ad hoc descriptions, eg listing what happens at each lead or noting the number of leads between calls. Where there is a framework, then it is possible to define calling positions within the framework and use these to define the touch. Long multi course touches are usually set out in a way that makes visible the similarities and differences between courses.

Many touches are defined in terms of what the observation bell (usually the tenor or the highest working bell) is doing at the calls. In doubles there is only one position that does not affect the 5th, and only a limited range of touches. It is common practice to call different bells as observation so the concept of fixed calling positions is less meaningful. Most methods (those based on Plain Bob) on higher numbers use a common scheme. It is illustrated in the table below for 2nds place even bell methods.

Each column lists all the positions of the tenor at leads [206]. They are aligned to show how the same names for calling positions are used with different numbers of bells. The work in brackets is what would have been done if there had been no call. Notice that some of the calling position names work from the back, while others work from the front. The dodging positions on higher numbers shown without a name are not normally used as calling positions.

| Calling position | Minor | Major | Royal | Maximus |

| Wrong = W | 5-6 up | 7-8 up | 9-10 up | 11-12 up |

| 7-8 up | 9-10 up | |||

| 7-8 up | ||||

| 5ths = V | 5-6 up | 5-6 up | 5-6 up | |

| 4ths = IV (Make the bob) |

(3-4 up) Make 4ths |

(3-4 up) Make 4ths |

(3-4 up) Make 4ths |

(3-4 up) Make 4ths |

| Before = B | (2nds) Run out |

(2nds) Run out |

(2nds) Run out |

(2nds) Run out |

| In = I | (3-4 down) Run in |

(3-4 down) Run in |

(3-4 down) Run in |

(3-4 down) Run in |

| 5-6 down | ||||

| 5-6 down | 7-8 down | |||

| Middle = M | 5-6 down | 7-8 down | 9-10 down | |

| Home [207] = H | 5-6 down | 7-8 down | 9-10 down | 11-12 down |

For the calls on the back you can see that for (n) working bells:

H = call at which tenor is in (n)ths place

W = call at which tenor is in (n-1)ths place

M = call at which tenor is in (n-2)ths place

In some methods, eg Kent, where the tenor is affected by a call, then the call is made so that it becomes (n)ths, (n-1)ths, (n-2)ths etc.

With methods on odd numbers of bells there is a problem. Many older books use the rule above, but since conducting by coursing order has become much more widespread, a different convention has also grown up based on what the call does to the coursing order. This means that the meaning of M and W in Bob Triples for example can be the opposite way round. It is always a good idea to check which convention is being used before you start to call a touch. It can be embarrassing to find out part way through that it is not what you thought. The effect of the calls on the coursing order is described below (see section 13.11j).

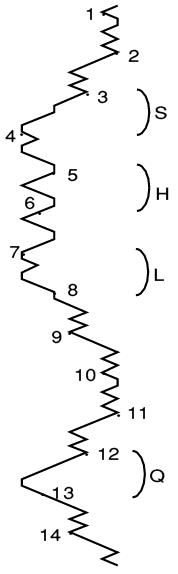

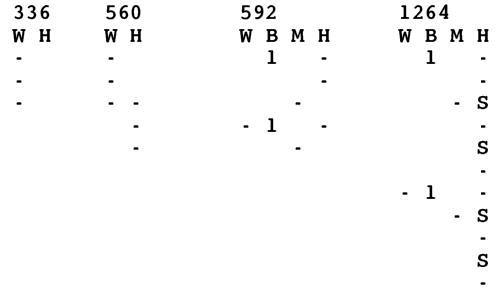

No. Methods like Stedman just number the calling positions from the beginning of the method (for the highest working bell). This is shown for Stedman Triples in the diagram. If you ring on higher numbers of bells you have to remember different numbers for the points on the blue line.

No. Methods like Stedman just number the calling positions from the beginning of the method (for the highest working bell). This is shown for Stedman Triples in the diagram. If you ring on higher numbers of bells you have to remember different numbers for the points on the blue line.

Many touches of Stedman Triples use pairs of calls in adjacent calling positions. This helps composers to avoid falseness. Some people find it easier to ring because after a pair of bobs, the bells on the back go in the same way they would have done with no call.

The pairs of positions used are chosen not to affect the 7th. They are given names to help remember them. These are S, H, L and Q, where:

S = slow ('in slow' and the following six),

H = half (both half turns),

L = last ('last whole turn' and the following six),

Q = quick ('in quick' 'out quick').

The positions are shown on the blue line, right.

The coursing order is most useful on higher numbers [208] of bells. Traditional calling methods were based on checking the lead heads, but that has been largely supplanted [209] by using the coursing order. Checking the coursing order [210] tells you if you are ringing the right course (ie that bells have not swapped over). It can help you correct mistakes and remind you where you are in the composition.

In methods like Plain Bob, you will see the coursing order as bells pass you almost twice every lead. In methods like Little Bob and Double Norwich you also see the coursing order continuously, but more slowly because the dodging means the bells take longer to pass you. In methods like Kent and St Clements, you continually see the order, but with the bells on the front missing. In methods like Yorkshire your course and after bells keep popping in and out of the sequence, so you must mentally remove them to see the real order. Also in such methods there are portions of the blue line where the order is swapped round, so you need to un-swap it mentally. In some parts of some methods the degree of un-swapping needed can be confusing. For more details see Conducting and Coursing Order.

Every call changes the coursing order, so you must either work out the new one each time (preferably just before in case something goes wrong at the call) or pick up the new order by seeing how you meet the other bells (risky if there is a mix up before you pick it up). To work out the new coursing order, you must transpose it unless you are able to visualise what everyone is doing.

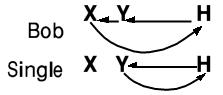

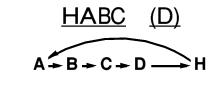

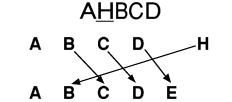

A bob moves three bells in the coursing order and a single moves two. A bob at the end of the first lead of Plain Bob changes the coursing order from 53246 to 32546. A single at the same place changes 53246 to 23546. The bells affected are underlined. The same group is affected at a bob or single. The general rule here is that a bob changes ABC ' BCA and a single changes ABC ' CBA.

You can think of this pictorially as:

At different leads different groups of three are affected.

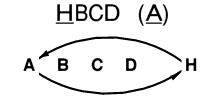

In methods with Plain Bob lead order, the group moves one place earlier each lead. The diagram shows this for Major with the affected bells underlined.

Be careful if the group of three bells affected includes the tenors. For example, a Before in Major moves the 6th, changing 8753246 to 8765324 (keeping the 8 at the beginning). This looks like a 'backwards' transformation on the last five, ie 8753246 to 8765324 . In Minor, on a smaller scale, 65324 becomes 65432. This is like 65324 to 65432. So a before is the opposite of a 'Home'. (And an 'In' is the opposite of a 'Wrong'). You can use this to vary touch length 'on the fly'. See section 13.11v.

| W | 8753246 |

| V | 8753246 |

| IV | 8753246 |

| B | 8753246 |

| I | 8753246 |

| M | 8753246 |

| H | 8753246 |

| Bells affected |

The transformation for a Before in Major is: ![]()

If you do the transformation above (ABC ' BCA) then A makes the bob, B runs out and C runs in. At a single (ABC ' CBA) then A still makes the bob, B makes 2nds unaffected and C makes the single (3rds and back). Draw out the structure if you are unsure and see how the bob changes the order. Remember that the coursing order is the order the bells follow each other up and down so look at the order they approach the lead and the order they leave it after the call.

When ringing doubles this is not normally a problem. Most touches are not defined round the tenor. You either remember where you are at the calls [212] or you keep an eye on what the observation bell is doing. This is easier with only four working bells (you and three others).

On higher numbers touches are usually designed around the tenor. It is harder if you don't ring round the back end, but there are ways of calling from other bells.

The structure of Grandsire in the plain course is similar to Plain Bob, but with two hunt bells and all the work moved up one place (2nds becomes 3rds, 3-4 becomes 4-5, etc). This means the coursing order throughout the plain course is only constant if the treble and 2nd are left out (ie 75346 for Triples). Doubles is again a special case (see section 13.11d). Here we describe Triples and above.

Calls affect the bell in the hunt, so you must allow for this when transposing the coursing order at a call. Calls that keep 7th out of the hunt are very simple and resemble those described for Plain Bob based methods (see section 13.11i & j).

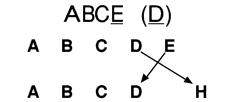

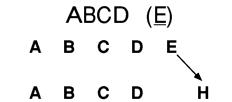

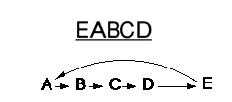

For simplicity the coursing orders omit the 7th which is assumed to be at the beginning of the order, and they show the hunt bell separately at the end. The coursing order before each call is ABCD (H).

For simplicity the coursing orders omit the 7th which is assumed to be at the beginning of the order, and they show the hunt bell separately at the end. The coursing order before each call is ABCD (H).

Those with the 7th in 5ths place or above involve transformations as shown. Which pair are X and Y (out of ABCD) differs from lead to lead as shown below

| Position of 7th | Call name | Effect of bob | Effect of single |

| 5th | Wrong* | BHCD (A) | AHCD (B) |

| 7th | Home | ACHD (B) | ABHD (C) |

| 6th | Middle* | ABDH (C) | ABCH (D) |

*We have used the Wrong and Middle definitions based on the effect on the coursing order. Traditional definitions would be the other way round.

Calls putting the 7th in 3rds place at the lead head ie a 'bob before' or 'making the single' bring the hunt bell to the beginning of the sequence.

| Position of 7th | Call name | Effect of bob | Effect of single |

| 3rd | Before |  |

|

Calls taking the 7th into or out of the hunt are a little more complex.

| Position of 7th | Call name | Effect of bob | Effect of single |

| 4th | Out |  |

|

| 2nd | In |  |

|

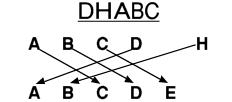

When the 7th is in the hunt at a plain lead, the lead end work by the other bells affects the coursing order as seen by the 7th so you must do the transformation EABCD

When the 7th is in the hunt at a plain lead, the lead end work by the other bells affects the coursing order as seen by the 7th so you must do the transformation EABCD

Stedman does not have a simple coursing order. The order that bells go in every other six stays constant. There are transpositions for this order, but they are much more difficult to remember and do in your head.

In approximate order of increasing difficulty:

Don't worry that you can't do all in this list. Most ringers can't, but just doing the first one could make the difference between firing out or not. The more you conduct, the more you will find you can sometimes do more of these things.

You should be able to see what the bell working with you is doing, and if you know the method structure, you will also know what it is going to do next. But people often go wrong when they are not anywhere near you. With practice, you can develop a form of extended ropesight to help you see what other people are doing. Needless to say, you must be able to ring your own bell well enough to leave some of your mental resources over for doing so. Like any skill, you need to practise. Here are some specific exercises you can try. Start with easy ones.

You can use particular features of the coursing order as landmarks. When you are learning a composition, seek out the landmarks as well as just learning where to put the calls. As examples, these three rules apply to touches in The Ringing World Diary. 'Always miss out the Home when the 5th is coursing in its natural position' (standard calling), 'The blocks of Homes have a single if the 4th would make it and a bob otherwise' (quarter of Plain Bob Major), 'Call Homes until the 5th goes back into the hunt' (quarter of Grandsire Triples).

Until you become experienced, yes. Even when you are experienced, you will still need to prepare a difficult touch. You must know it thoroughly and learn where the landmarks are. Conduct it several times in your head without looking at the composition. You are more likely to find out whether you have made a mistake with the composition by going through it in your head than just looking at the figures on paper. Some people like a final rehearsal calling a quarter peal in their heads while walking to church.

Until you become experienced, yes. Even when you are experienced, you will still need to prepare a difficult touch. You must know it thoroughly and learn where the landmarks are. Conduct it several times in your head without looking at the composition. You are more likely to find out whether you have made a mistake with the composition by going through it in your head than just looking at the figures on paper. Some people like a final rehearsal calling a quarter peal in their heads while walking to church.

In some methods the coursing order is not so apparent and is less helpful, but it may still help you to understand what is going on while you are ringing.

This is a bit of a tricky one! Strictly speaking the lead end is the row at the handstroke of the treble's full lead and the lead head is at the backstroke. So what is often called a lead begins at the treble's backstroke lead (the lead head) and ends at the treble's handstroke. However, ringers often call the lead head the lead end. If the conductor says 'lead end now' he or she usually means the treble's backstroke lead. This is a bit confusing, but as a rule of thumb:

| Composers mean: | Ringers in general mean: |

| Lead end = treble's handstroke lead Lead head = treble's backstroke lead |

Lead end = treble's backstroke lead (They don't use lead head). |

Most methods have portions where the coursing is more or less visible (eg 3rds place bell in all methods with Cambridge above the treble). In many methods a lot of your work is with your course bell or after bell (eg Bristol Surprise Major), even if the rest of the coursing order is less visible. In fact providing you make special cases of your course and after bell (ie you note that there are some extra times when you will meet them) then the remaining order often looks much more like normal coursing order than it does at first sight. For example, this is true of all of Yorkshire except parts of 2nds place bell and its mirror image 5ths place bell, where two pairs swap order.

There are many sources. The Ringing World Diary contains a selection of short touches and quarter peals for many common methods from Doubles to Maximus. There are publications devoted to sets of compositions of various sorts, including Easily remembered Service Touches, The Bob Caller's Companion and Quarter 500. The Central Council maintains periodically updated lists of compositions. Many ringing books contain some touches.

Yes. You can experiment with pencil and paper to see what works. Although you will need a degree of trial and error, you should adopt some sort of methodical process rather than just putting in calls at random. We can't cover the whole theory here, just a few basic ideas.

With longer touches, you can insert round blocks without singling providing the calls will fit naturally between the calls of the basic touch. A round block is a block of calls that returns to where it began. Many peal and quarter peal compositions use this technique by inserting blocks of two, three, four or even six courses [219] at various points within a framework that would come round much sooner. For example, with Plain Bob Major blocks of Homes are often used.

With longer touches, you can insert round blocks without singling providing the calls will fit naturally between the calls of the basic touch. A round block is a block of calls that returns to where it began. Many peal and quarter peal compositions use this technique by inserting blocks of two, three, four or even six courses [219] at various points within a framework that would come round much sooner. For example, with Plain Bob Major blocks of Homes are often used.It depends why you want the touch. The rules for recognised peals require the composition to be true, and although the rules don't actually require it, most ringers expect quarter peals to be true (no rows repeated). Shorter touches for services and practice need not be, but the ethos of truth is deeply embedded in ringing tradition, so you are unlikely to see a false one published except by error.

In many ways this is a pity. As we noted above, the main driving force of most serious peal composers of Major and higher is to maximise the music while preserving truth. Where the two are mutually exclusive it is a shame that truth takes precedence over musicality.

This is an unanswerable question. Like everything else it will depend on a combination of aptitude, how much practice you get and how interested you are. The amount of practice could be very variable unless you and the ringing masters with whom you ring make a conscious effort to give you the opportunity to gain experience. You won't progress very far if you only conduct when there is no one better to do it. If no one else conducts in your tower, you will get lots of practice (but not much advice).

Several publications cover conducting, eg Conducting and Coursing Order, On Conducting, Conducting for Beginners, The Bob Caller's Companion and Will You Call a Touch Please Bob.

Currently hosted on jaharrison.me.uk